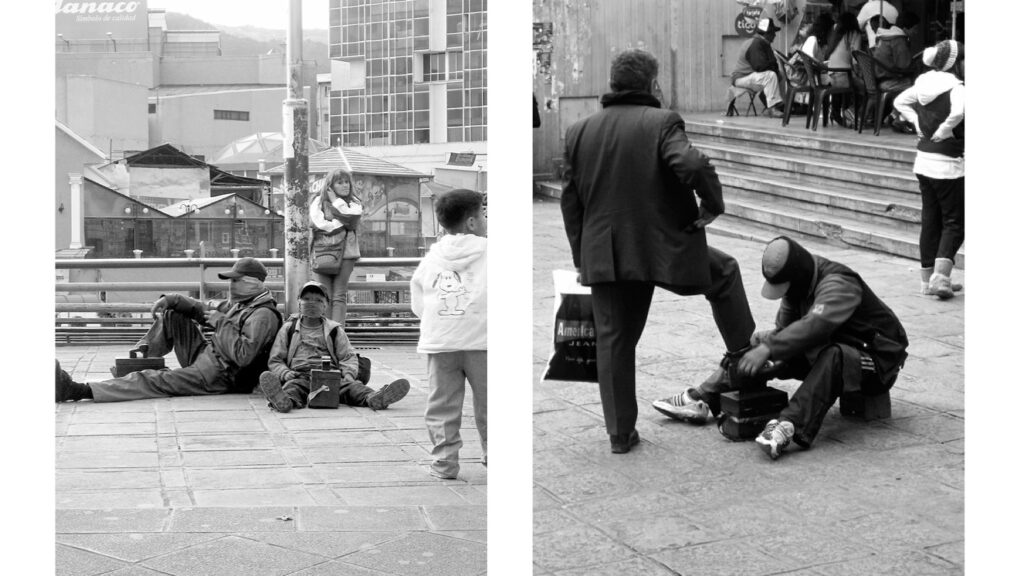

There are 3,000 shoe shiners who go out into the streets of La Paz and El Alto suburbs each day in search of clients. They are from all ages and, in recent years, have become a social phenomenon in the Bolivian capital.

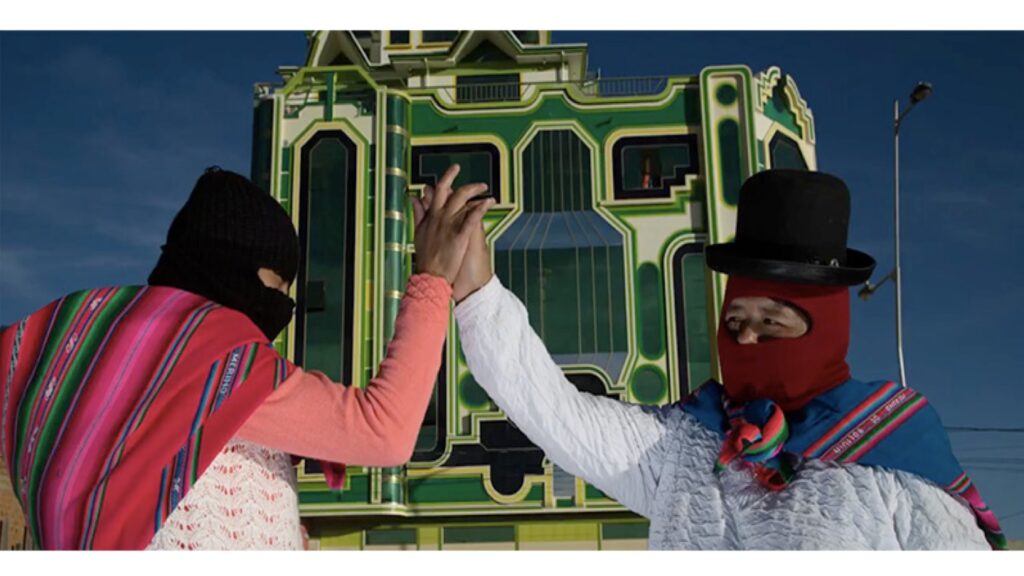

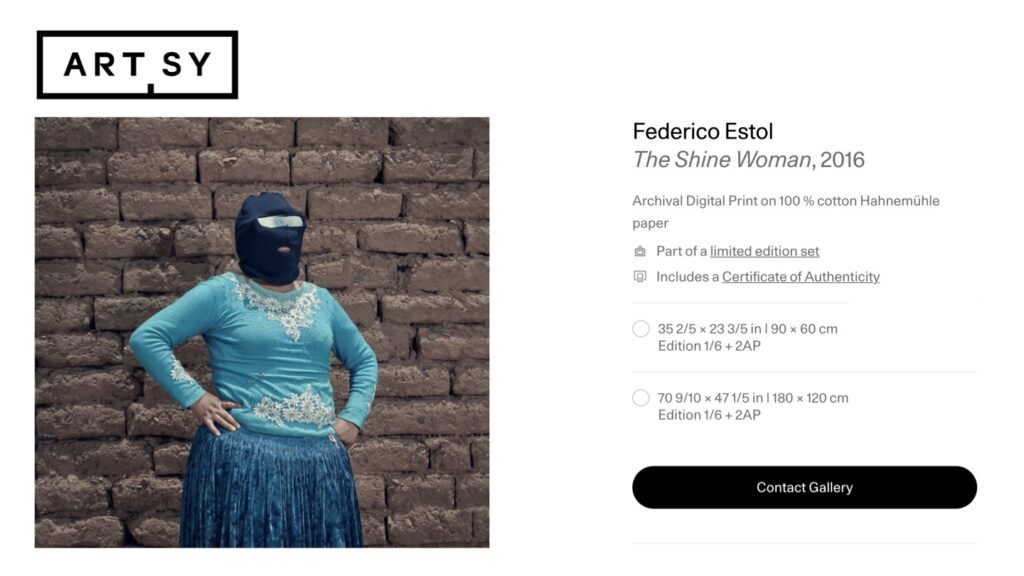

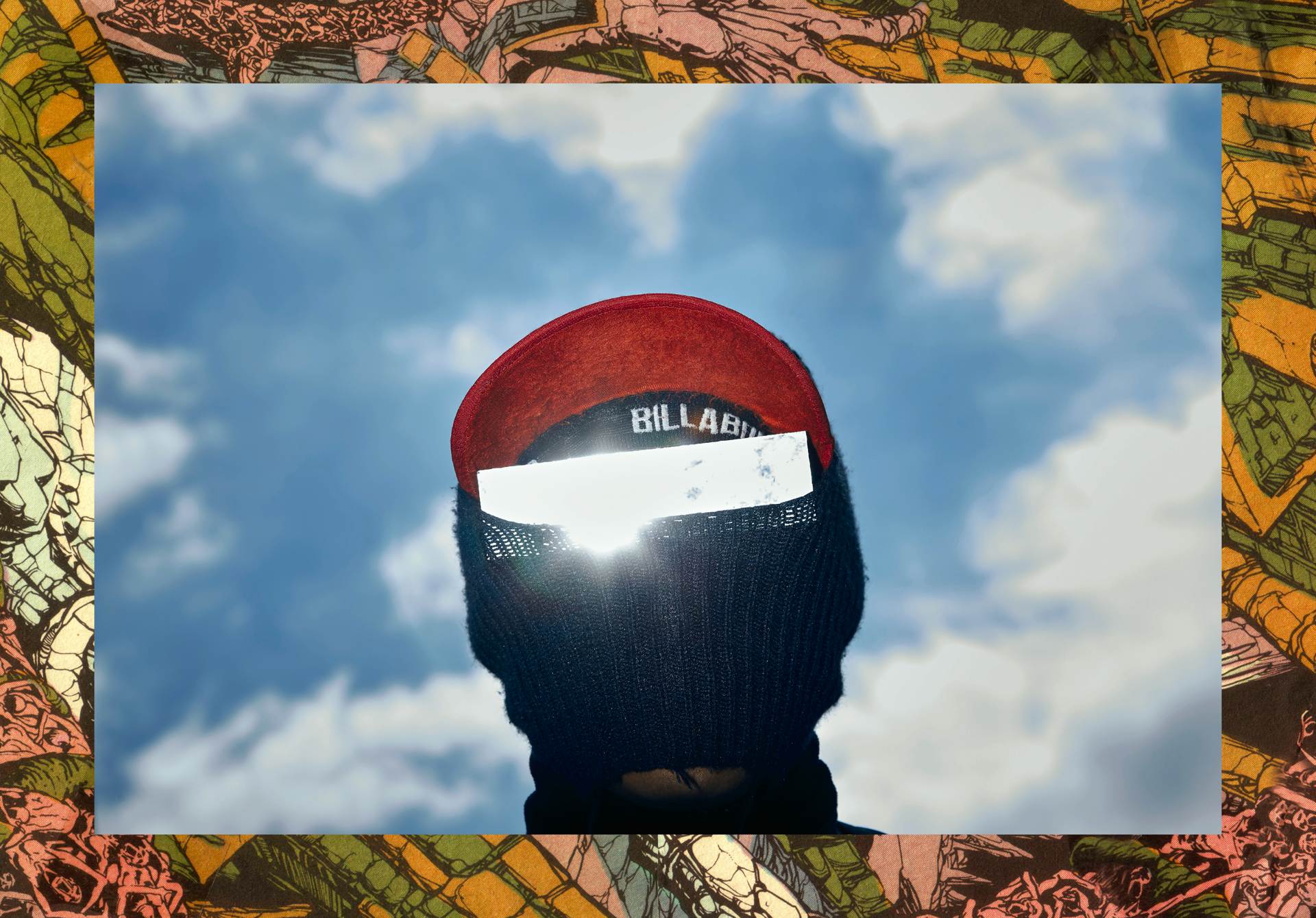

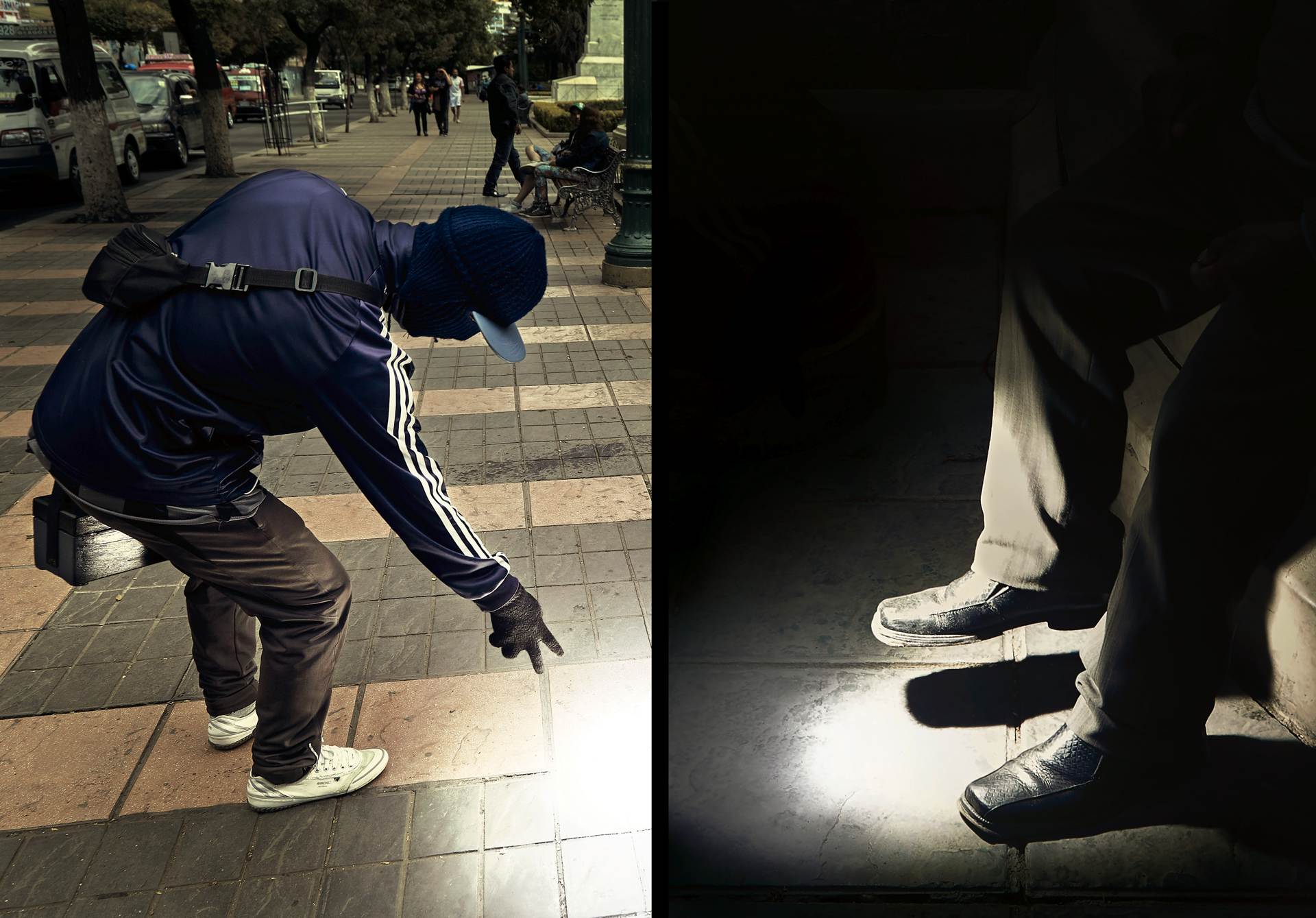

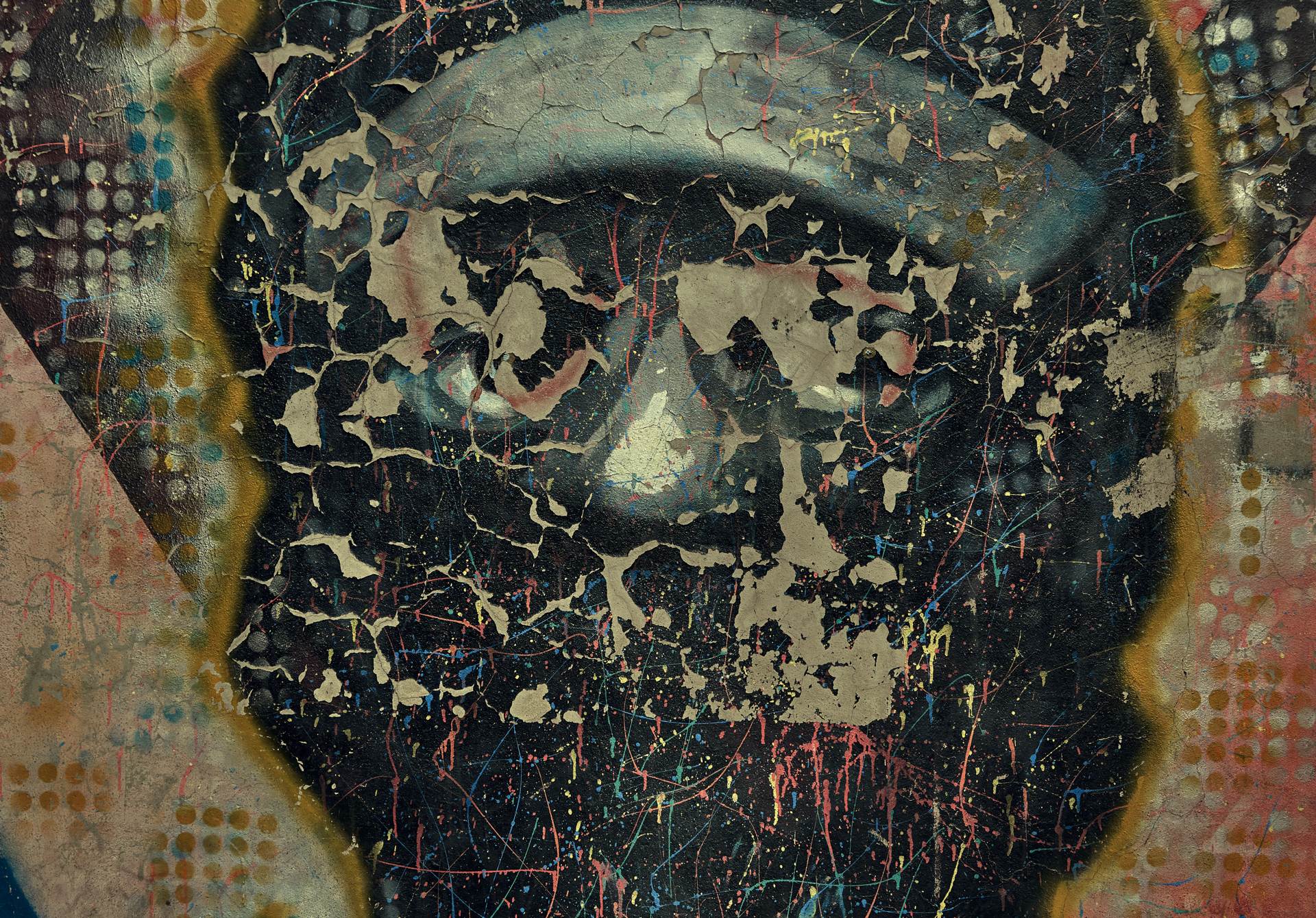

What characterizes this tribe is their use of ski masks to avoid being recognized by those around them. They confront the discrimination they face through these masks; in their neighborhoods, no one knows that they work as shoe shiners. At school, they hide this fact, and even their own families believe they have a different job when they head down to the center of the city from El Alto.

The mask is their strongest identity, making them invisible while at the same time uniting them. This collective anonymity makes them tougher when facing the rest of society and is their resistance against the exclusion they suffer because of their work.

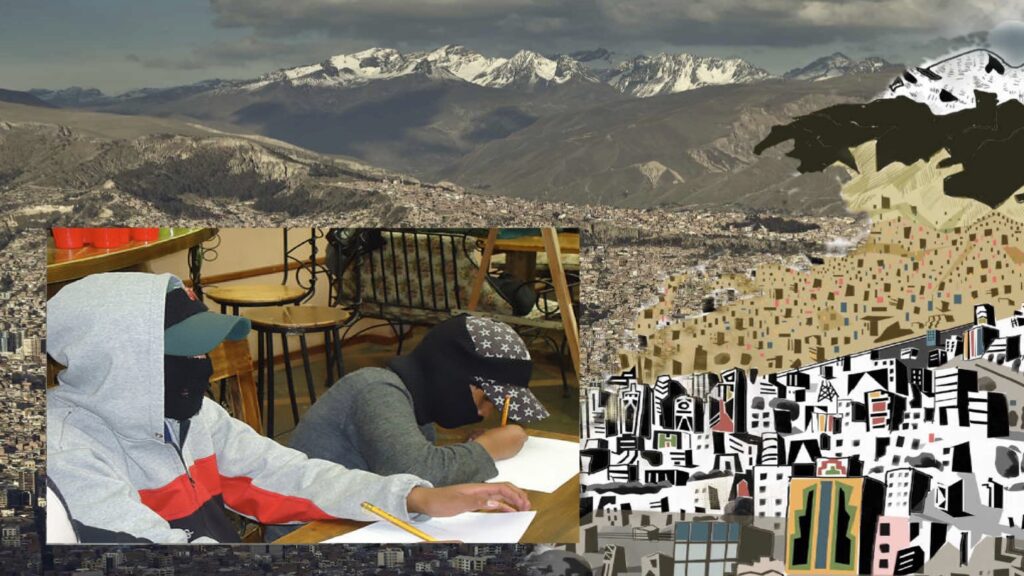

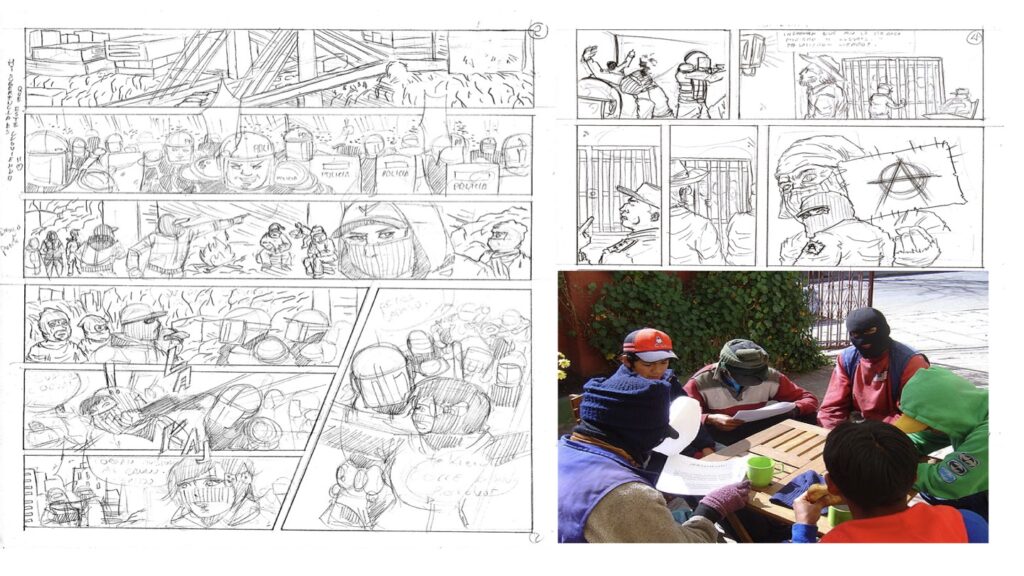

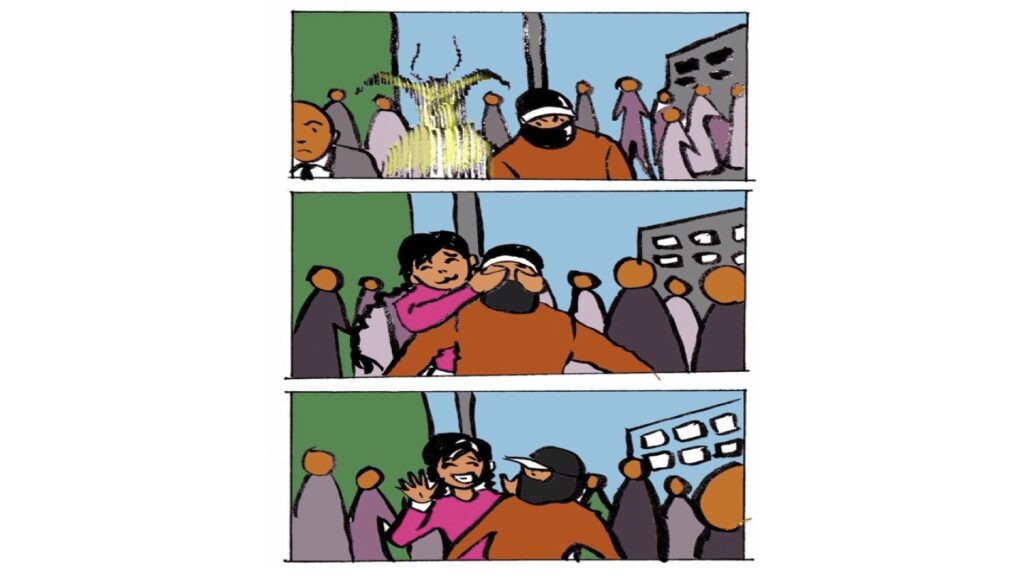

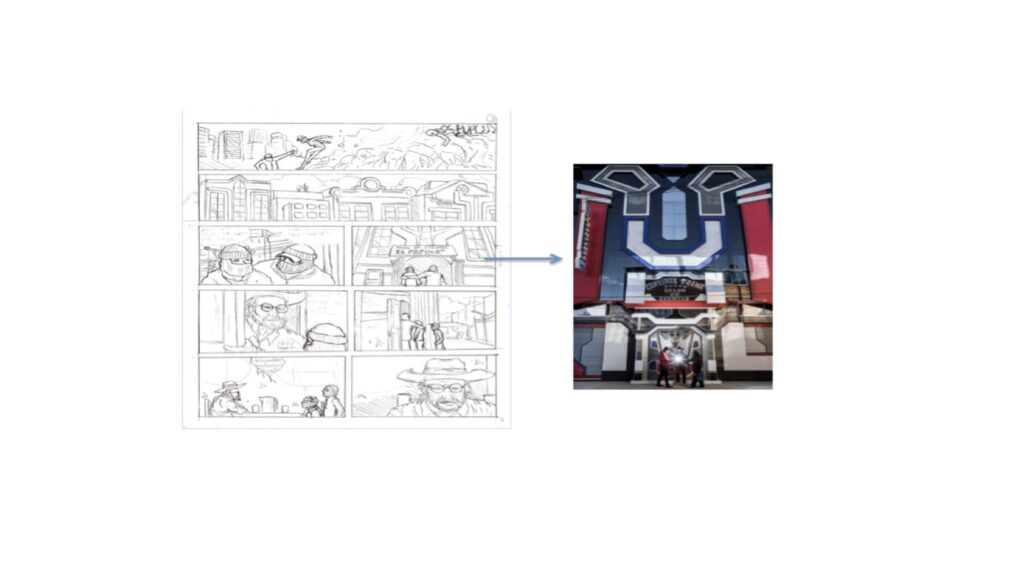

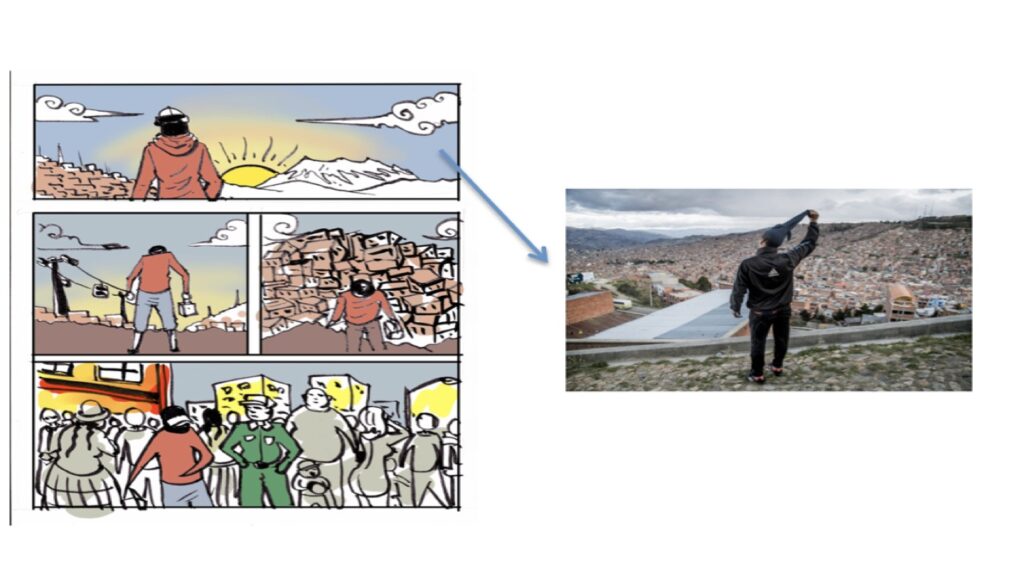

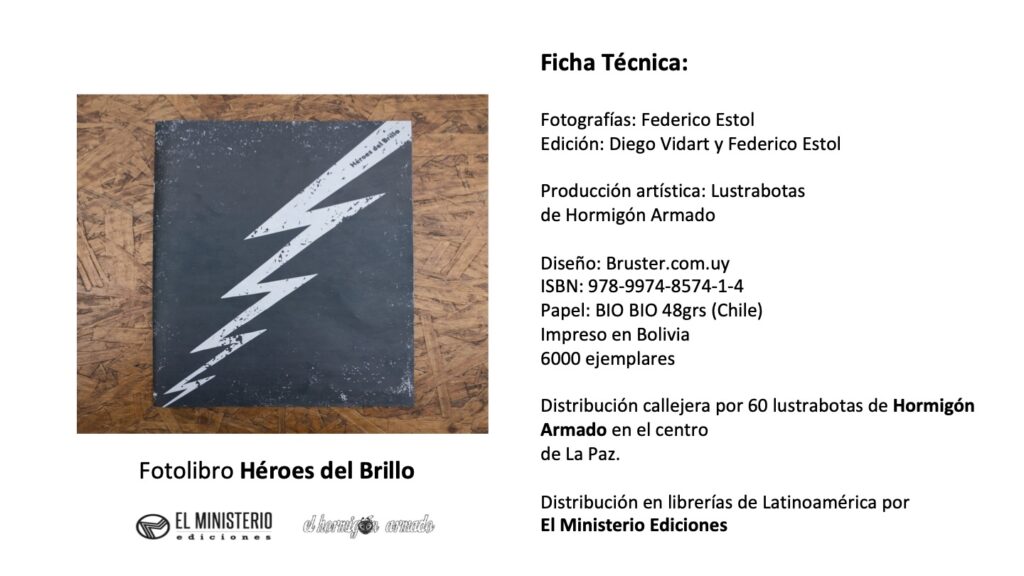

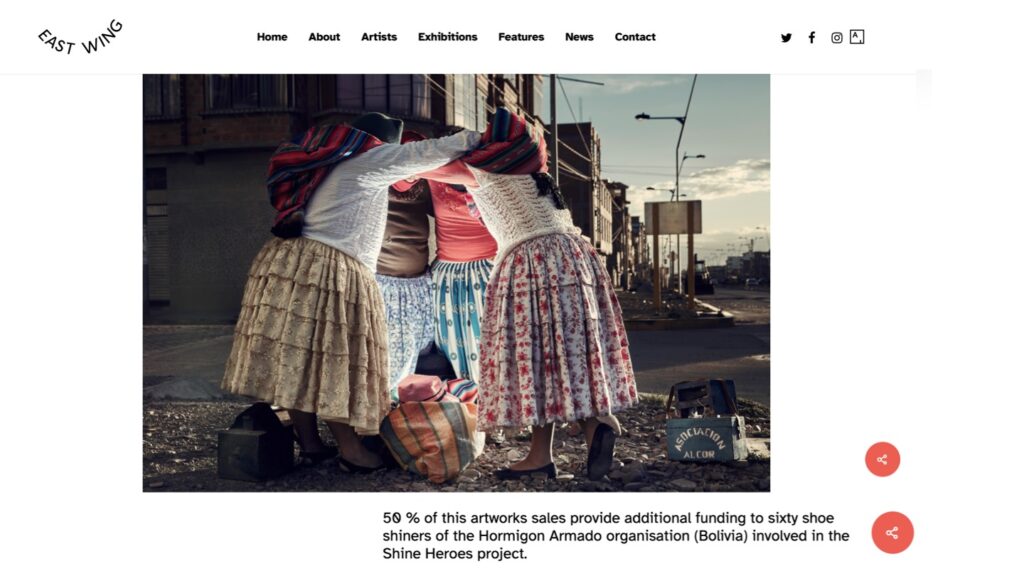

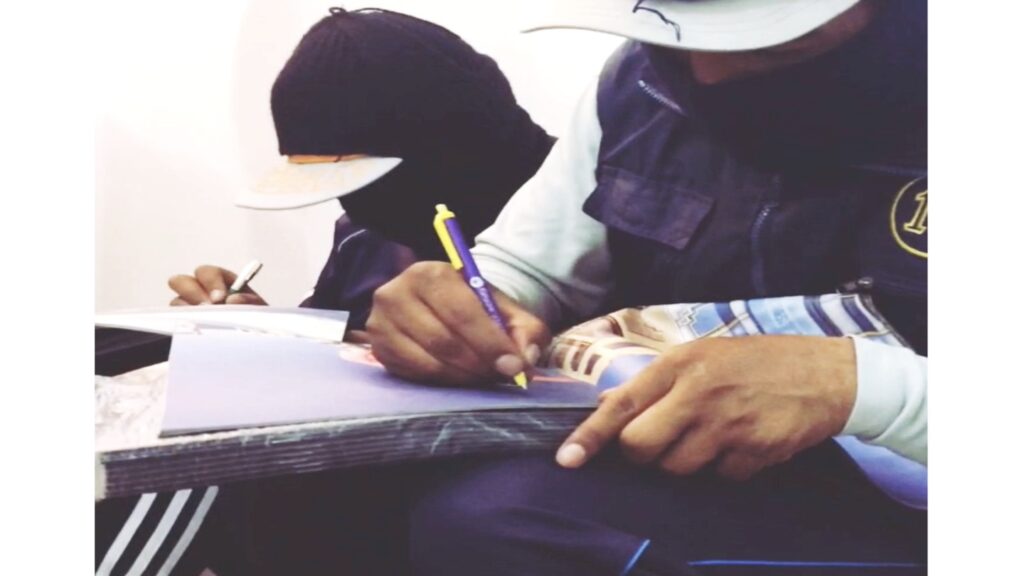

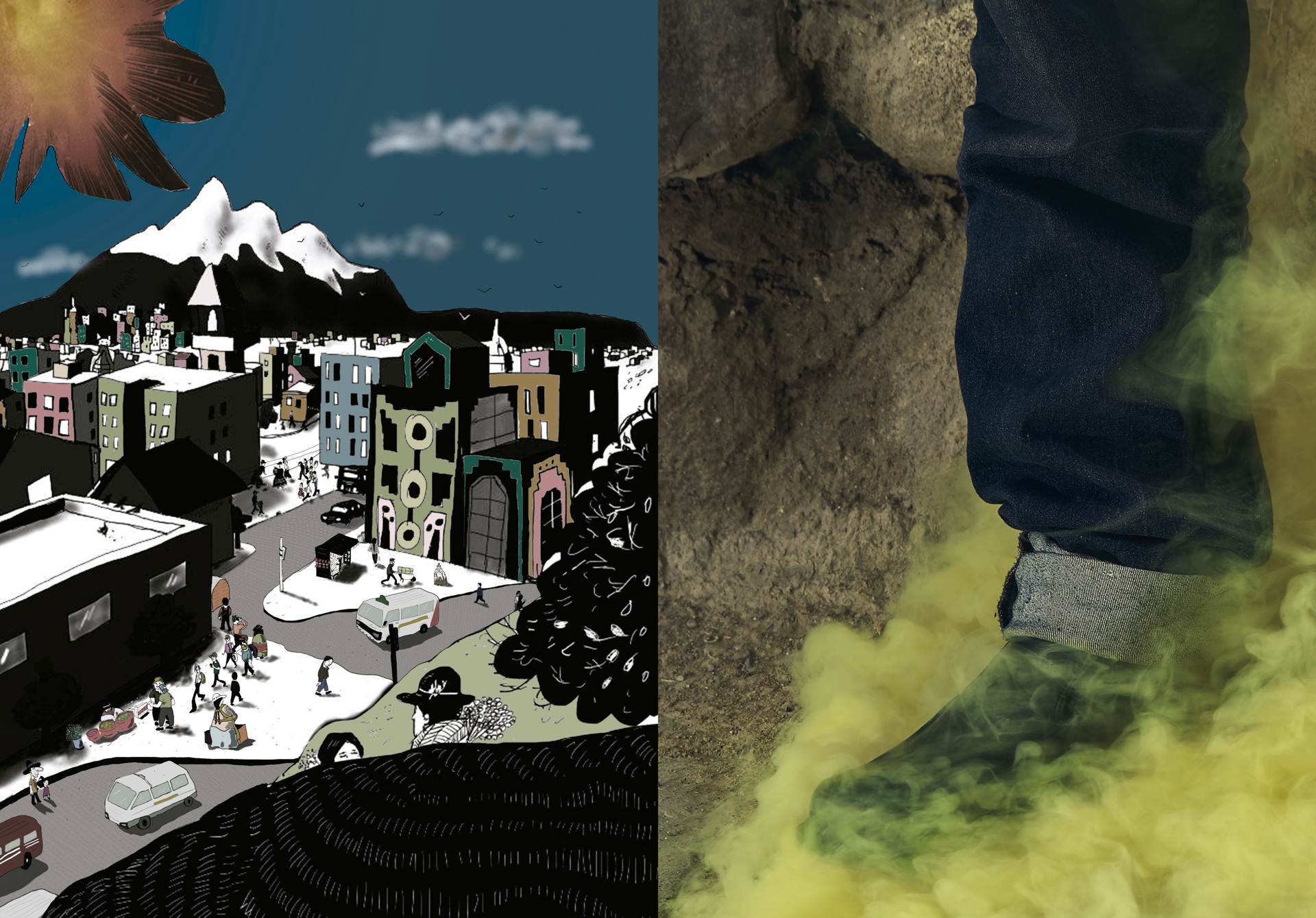

For three years Federico Estol has been collaborating with sixty shoe shiners associated with the organization "Hormigón Armado.” We planned the scenes together during a series of graphic novel workshops, incorporating local elements of the urbanity of El Alto and producing photographic sessions with them as co-authors of an emancipation photo-essay to fight against social discrimination.

The project:

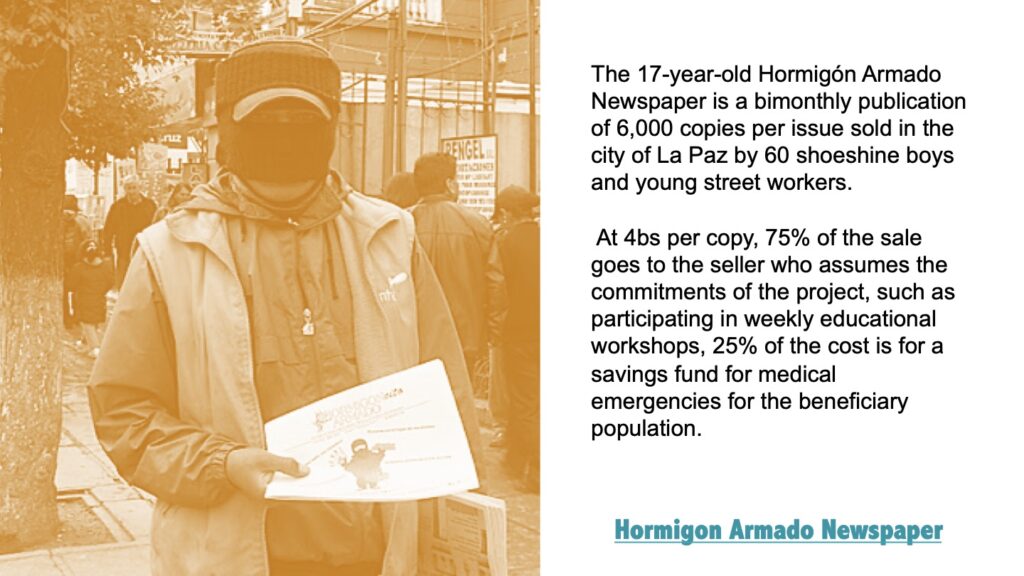

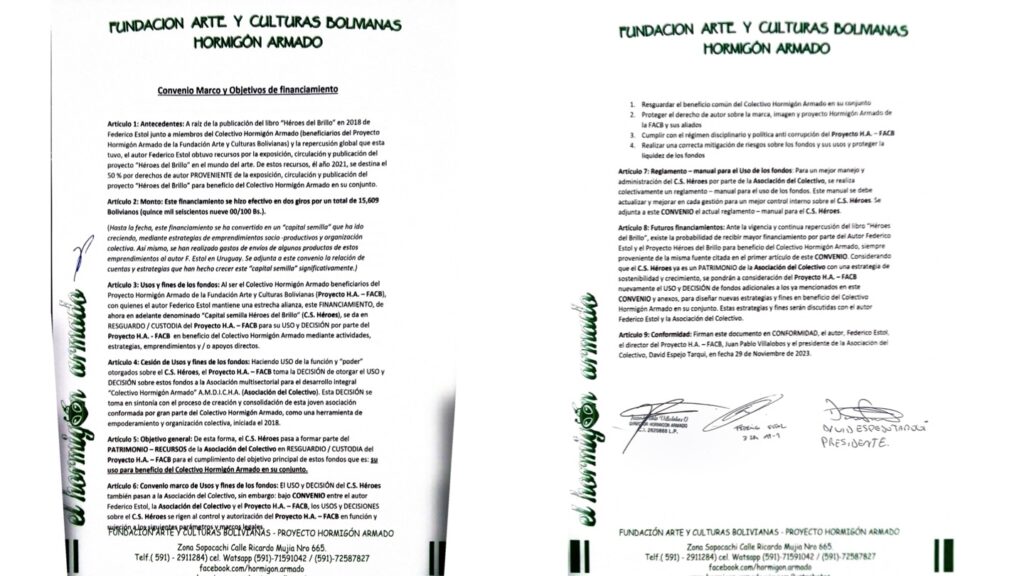

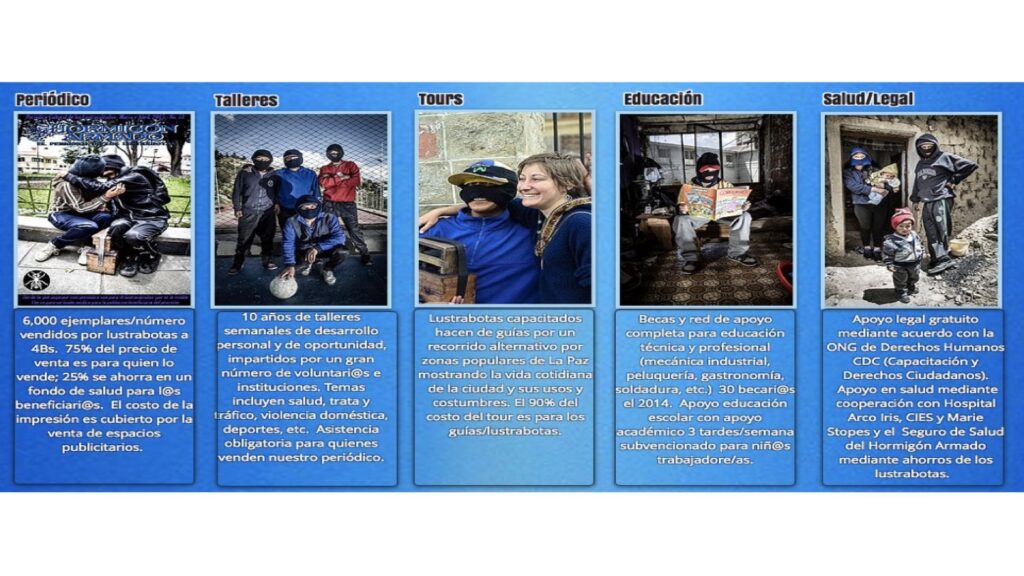

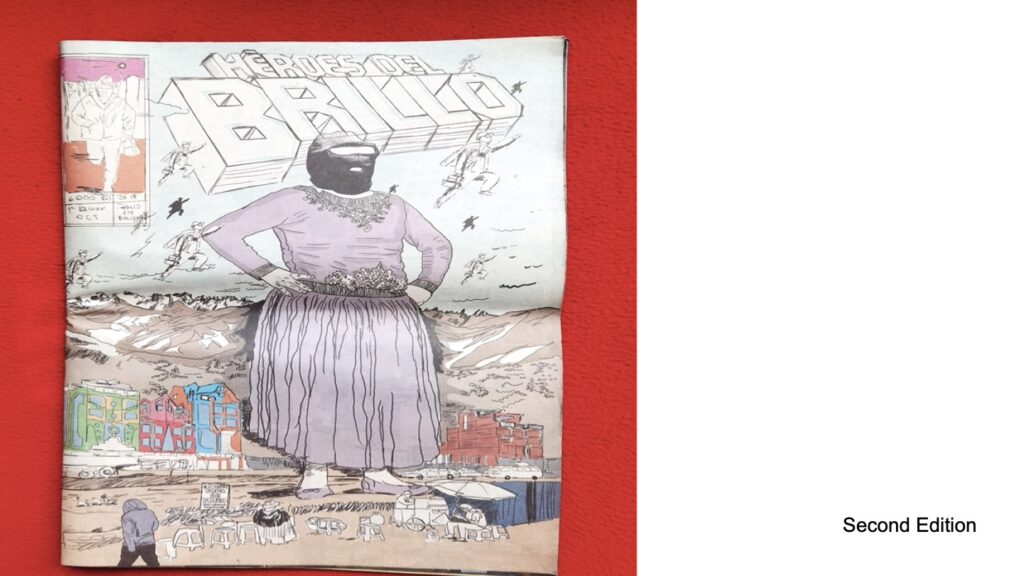

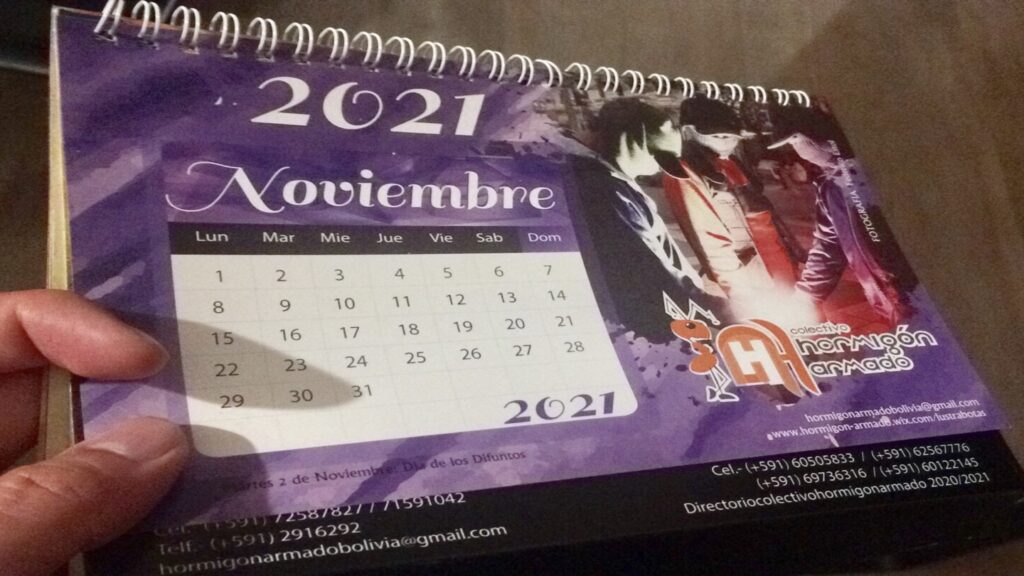

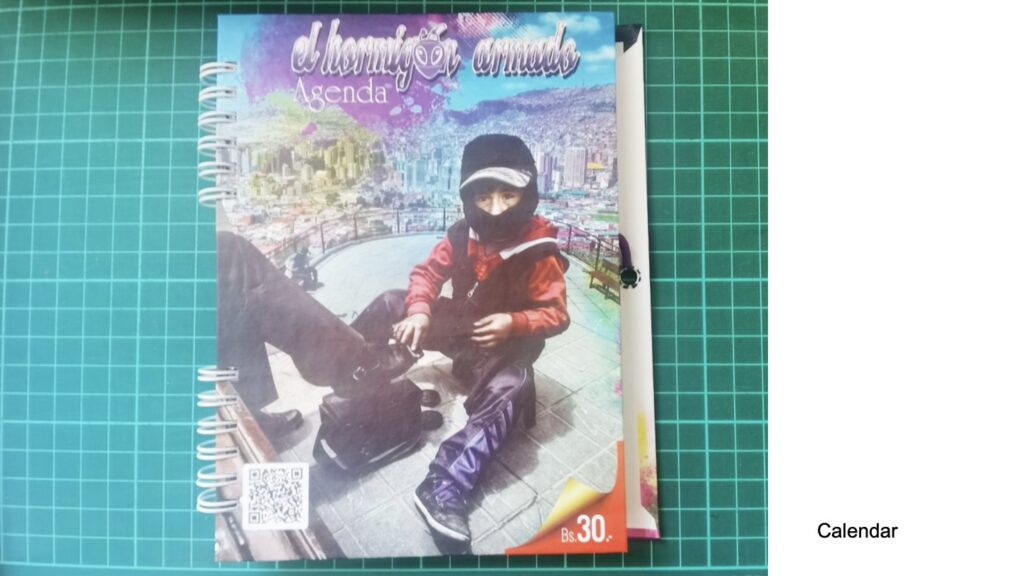

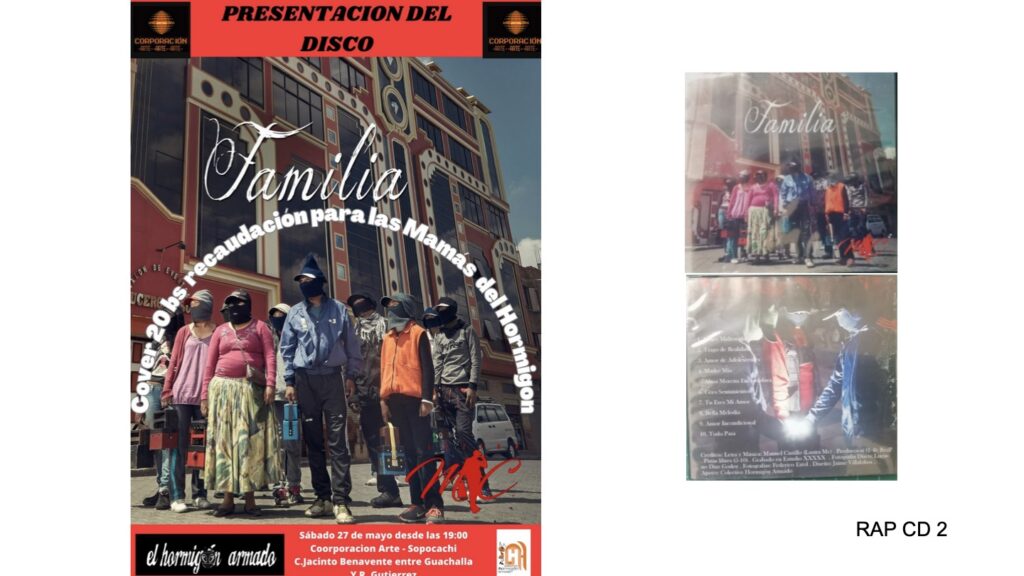

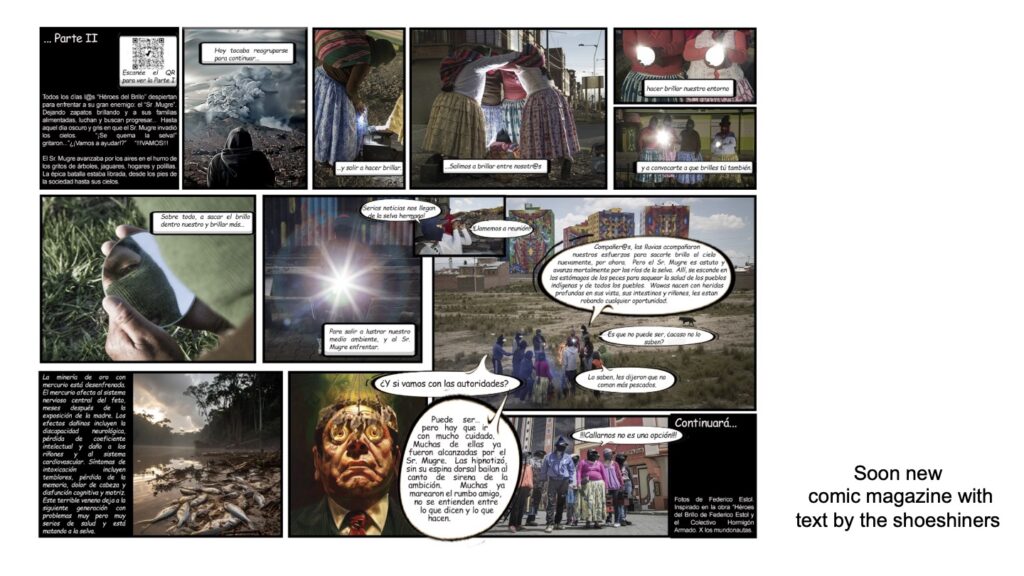

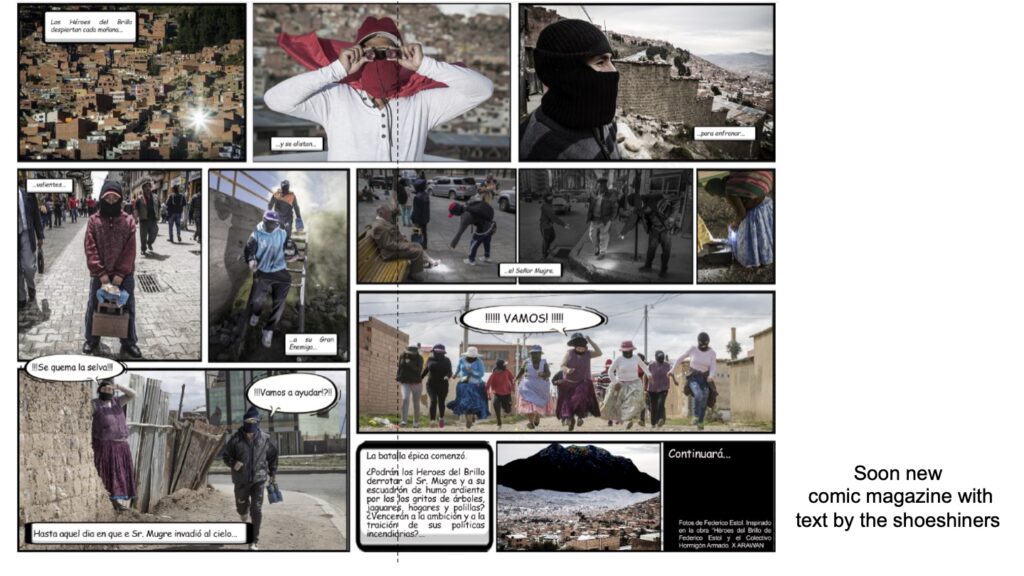

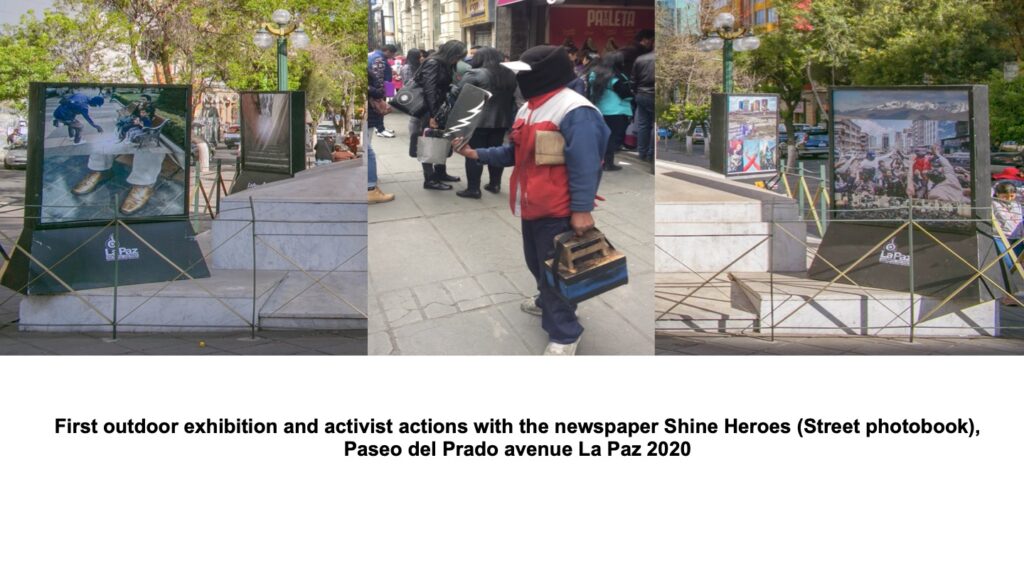

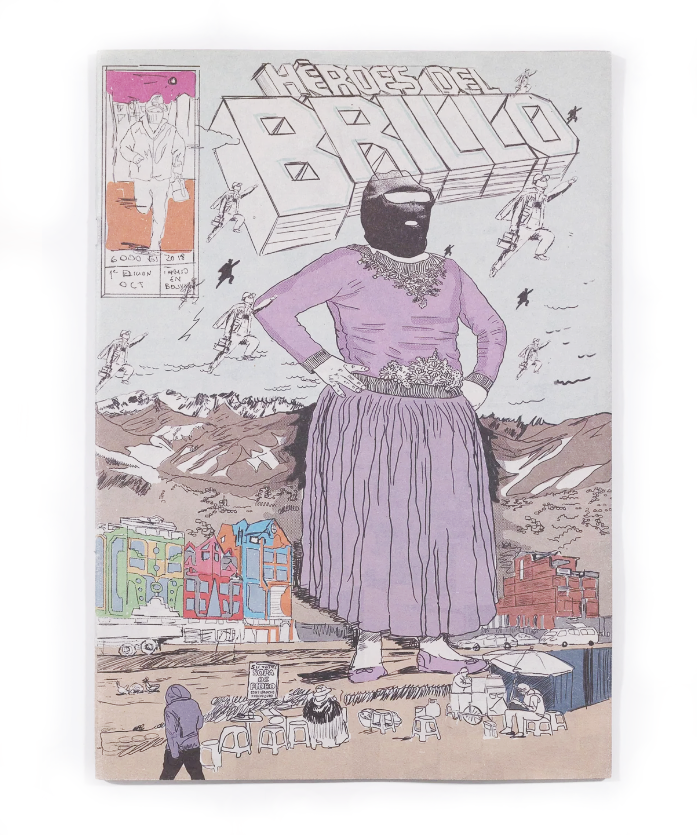

Sixteen years ago, Hormigón Armado launched a newspaper. Currently, 6,000 copies are sold each month, with the proceeds providing additional income to nearly 60 families of shoe shiners. Estol initiated a project to create a special edition of this newspaper through a participatory workshop. This process invited the shoe shiners to reimagine their story in creative new ways.

Over the last three years, Uruguayan artist Federico Estol has extensively collaborated with a group of shoe-shiners associated with the social organisation Hormigón Armado. This organization was established with a view to supporting the shoe-shining workforce.

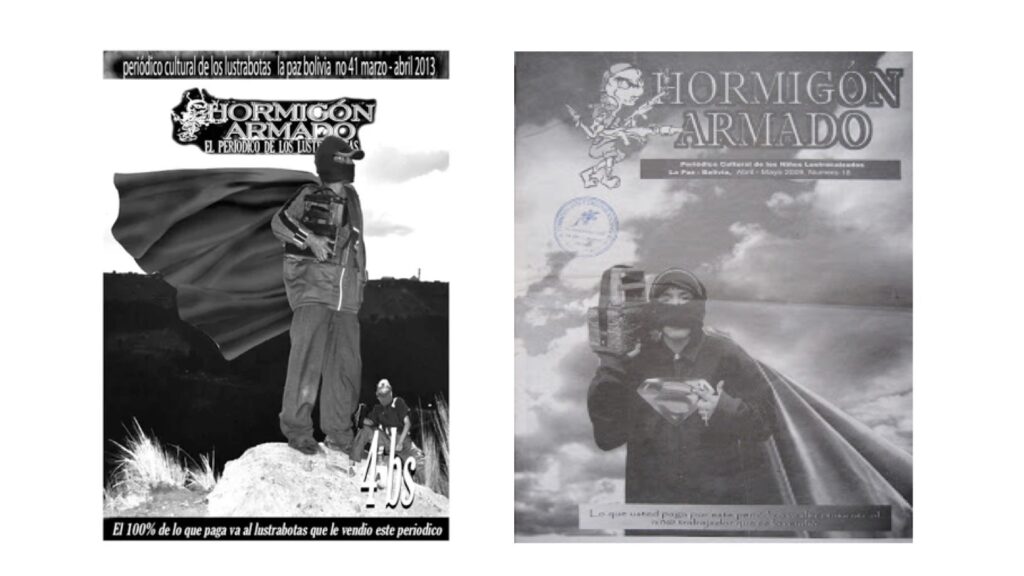

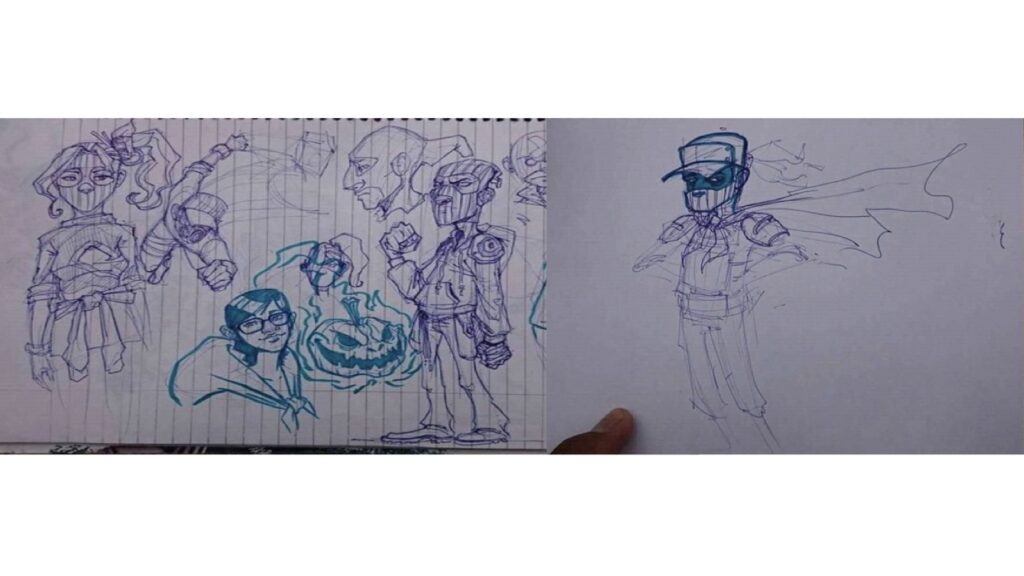

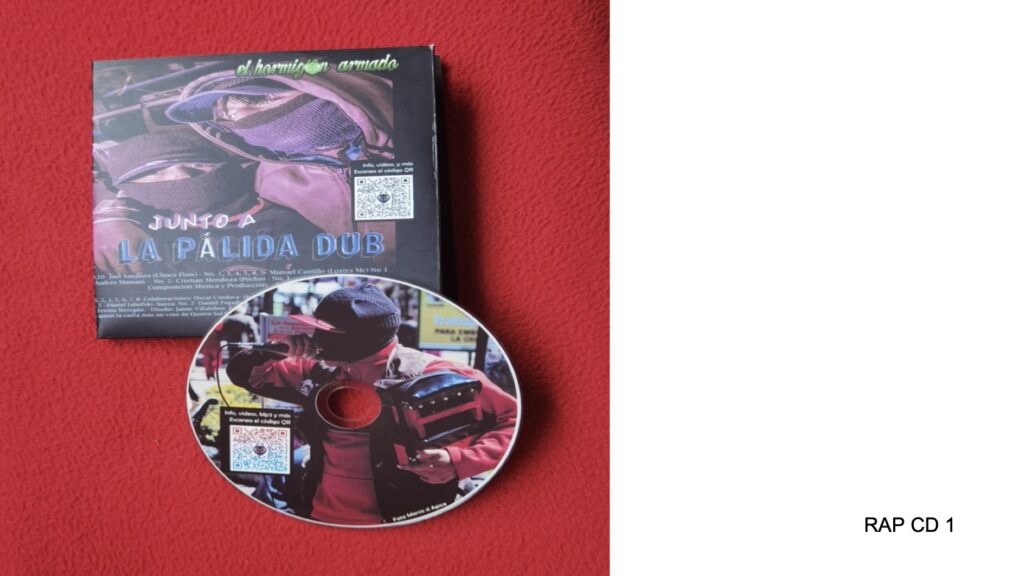

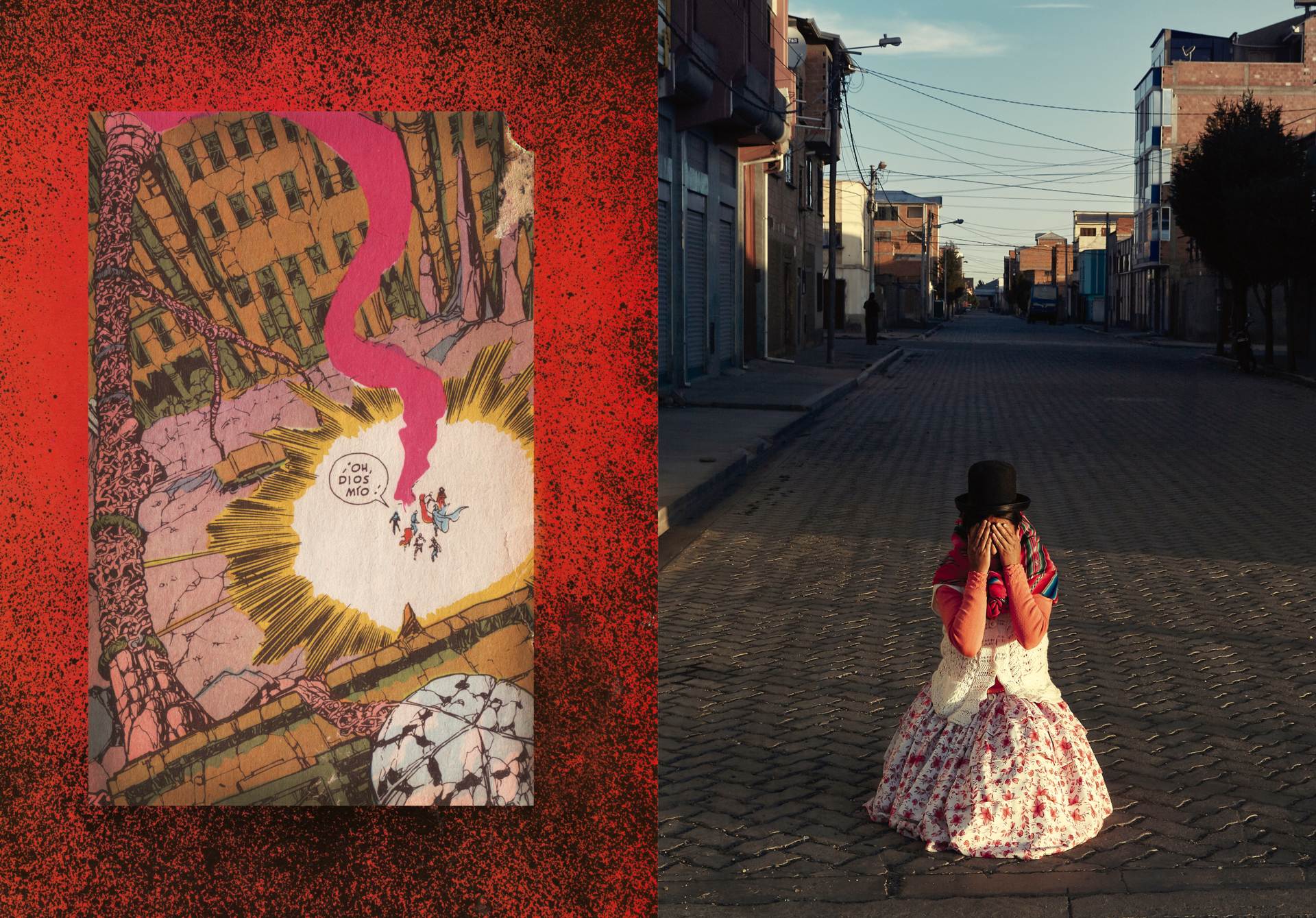

Drawing on the visual language of comics and graphic novels, and integrating elements of everyday life in El Alto, the resulting narrative portrayed the shoeshiners not as outcasts, but as urban superheroes responding to the unwavering local demand for polished shoes.

Initially, the group employed a documentary approach, but it proved unworkable due to the negative connotations associated with the balaclavas worn by the shoeshiners. When the images were shown, Bolivian citizens still viewed the shoeshiners as dangerous.

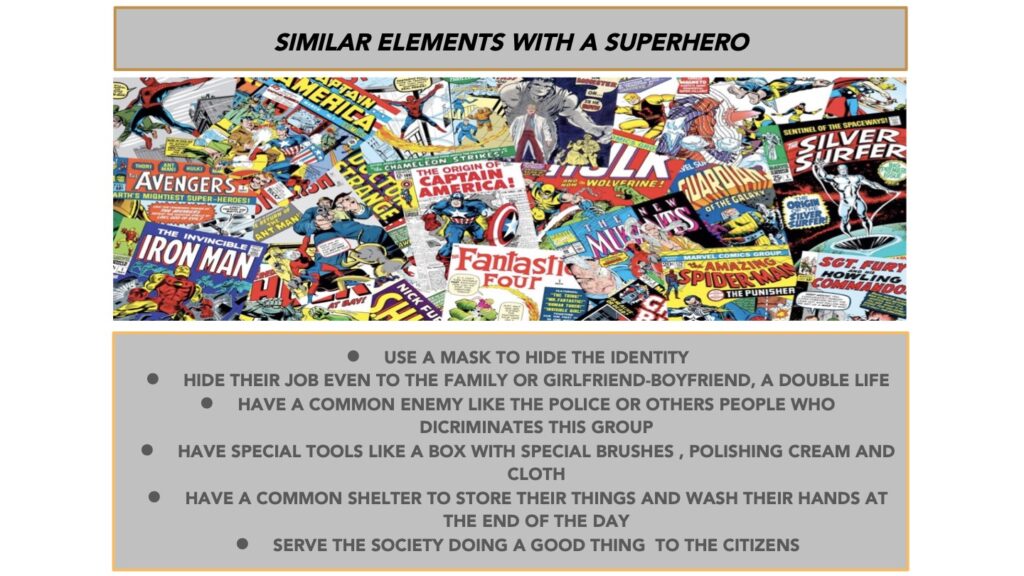

During the first year in the field, the group shifted to using fiction to avoid emphasising the discrimination they aimed to challenge. The shoe-shiners shared characteristics with superheroes: they wore masks in order to conceal their identities, used special tools, had a common shelter or bunker and upheld a character of righteous assistance by shining citizens’ shoes.

Ultimately, fictional photography was far more effective in transforming discriminatory attitudes than documenting reality.

Social methodology: